Simple Robotics Competition Traps Tryhard

Today were my national finals (the last stage before a Swiss grand finale and after a round of video-based preliminaries) of the Robotics for Good Youth challenge at the Mobile Congress.

challenge

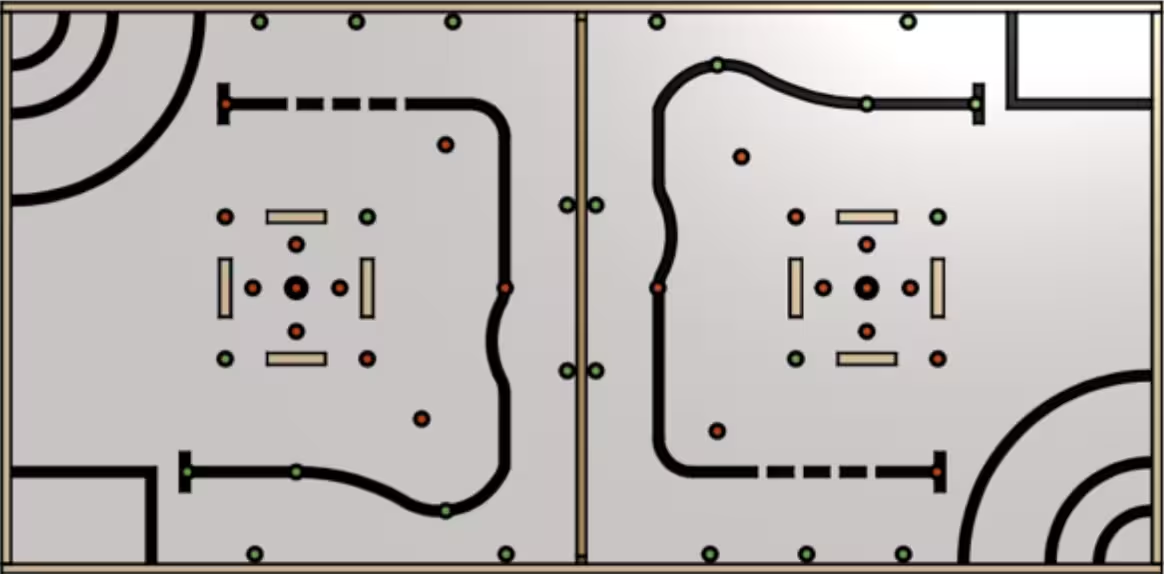

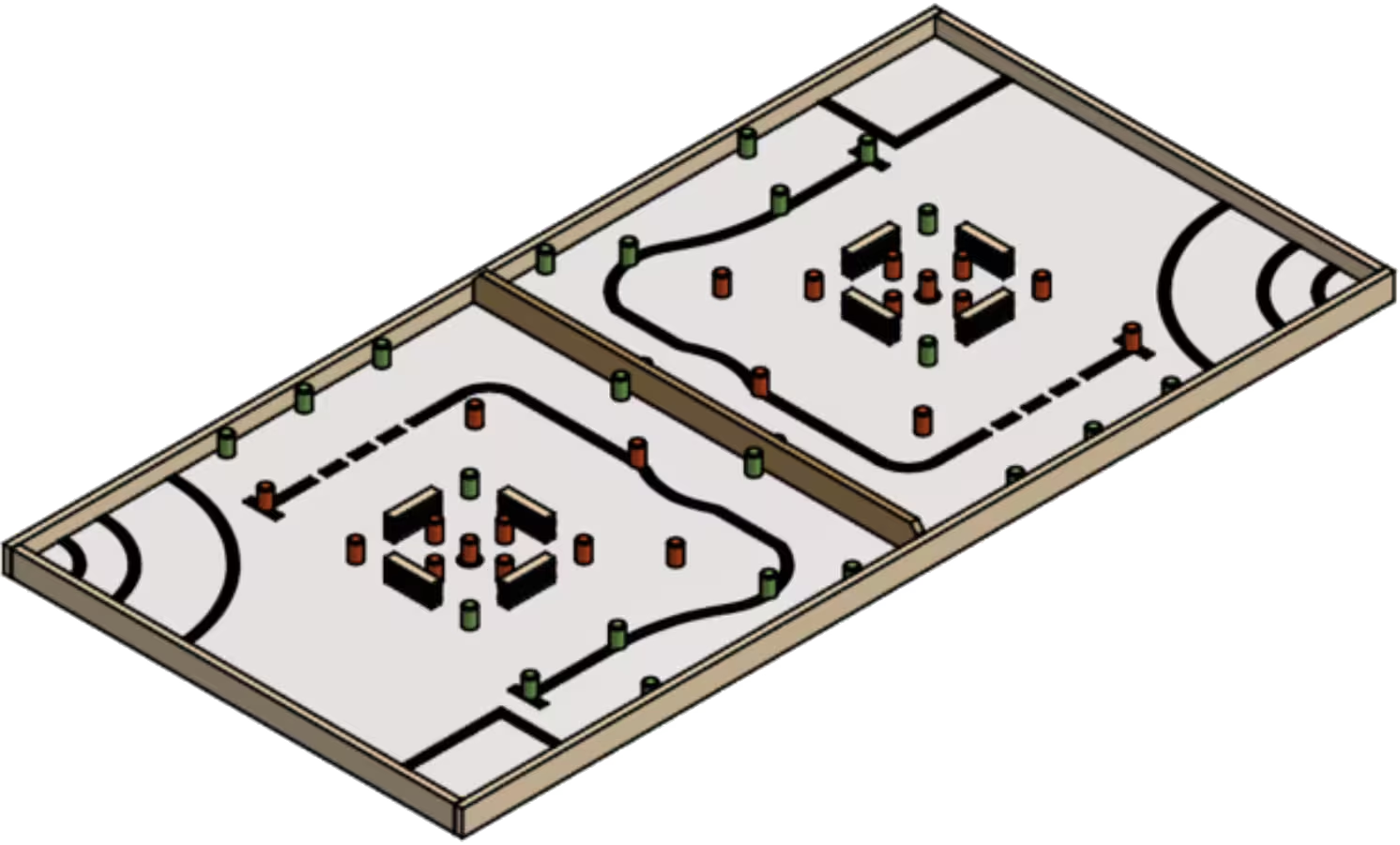

The challenge, an abstraction of a natural calamity scenario where technology would be needed for disaster response, was very well documented in an incredible rulebook, taking place on the game board, a large, precisely specified rectangle (roughly a 1.4 meter square), with all locations, dimensions, coordinates, colors, and materials given well in advance.

One corner of this flat board had a shelter, the adjacent corner a hospital, and the center was a “building” made of Jenga-like pieces of wood:

- Red cylinders (again, all very well specified) represented “injured” people who had to be moved into the hospital zone (a quadrant with a roof at the bottom left corner of the board), and

- Green cylinders represented “evacuees” who had to be taken to the shelter (a rectangular zone with a raised platform inside) at another, but

- Those near the center of the board needed extra care to prevent the “building” from collapsing.

prelims

To qualify for the in-person intranationals (which had timed 1v1 point-based rounds), teams had to submit a video demonstrating the development, progress, and working of their robots. I threw one together (the first design) of a big 2s li-po, a 3d-printed “taco” frame, two low-kV and high-torque BLDCs.

It was far from what I wanted to present it as, but with some selective cutting of chanced, opportune shots, I made a video of the partially functional and structurally flawed robot that looked polished next to an aggressive amount of smart nonsense narration and captioning. It did enough correct-looking things on camera for our Minimum Viable Lie to qualify via bullshitting.

v2

Coming next were the finals, in which every match, two teams were to compete simultaneously on mirrored boards. You were both to start at the same time and have 120 seconds for your robots to run, after which points were to be awarded (calculated as specified in the above rulebook, which listed exact points) based on how many blocks of each color your robot managed to get into their correct zones, and how deep they were placed.

We had some days before the finals after qualifying the prelims, and due to the structural issues of direct drive BLDC (never again) and large design of the existing robot, I decided to build an entirely new one.

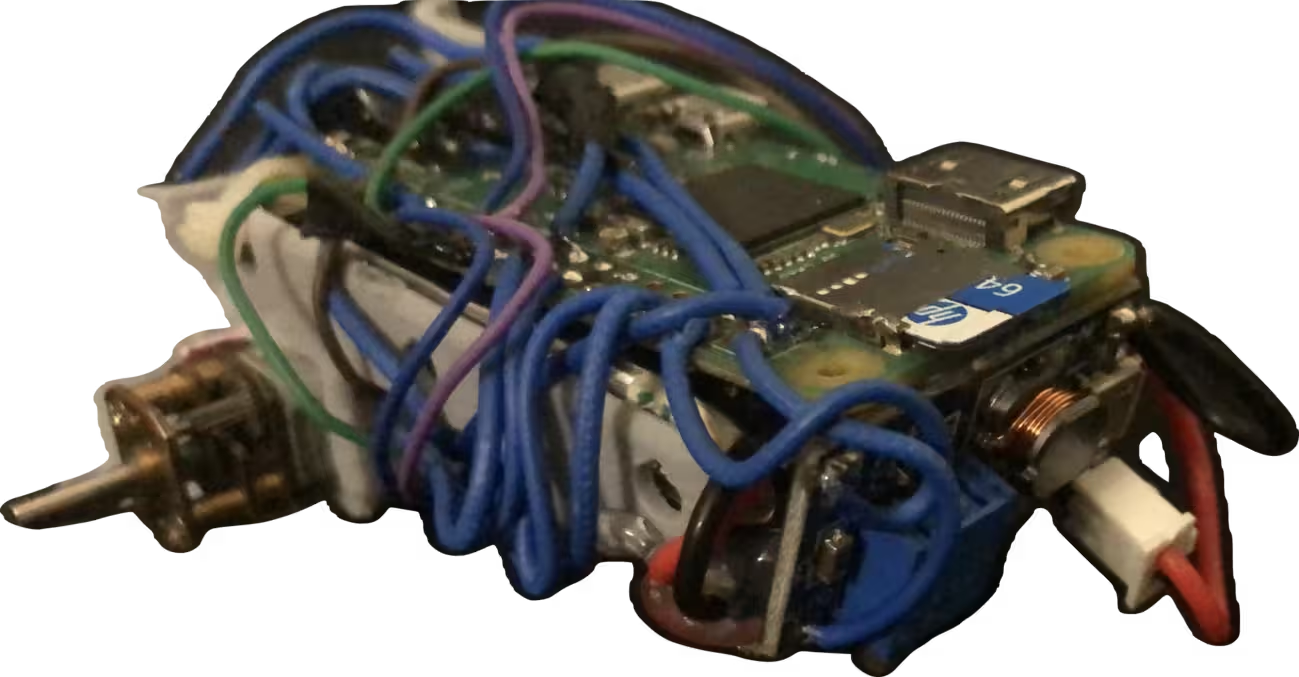

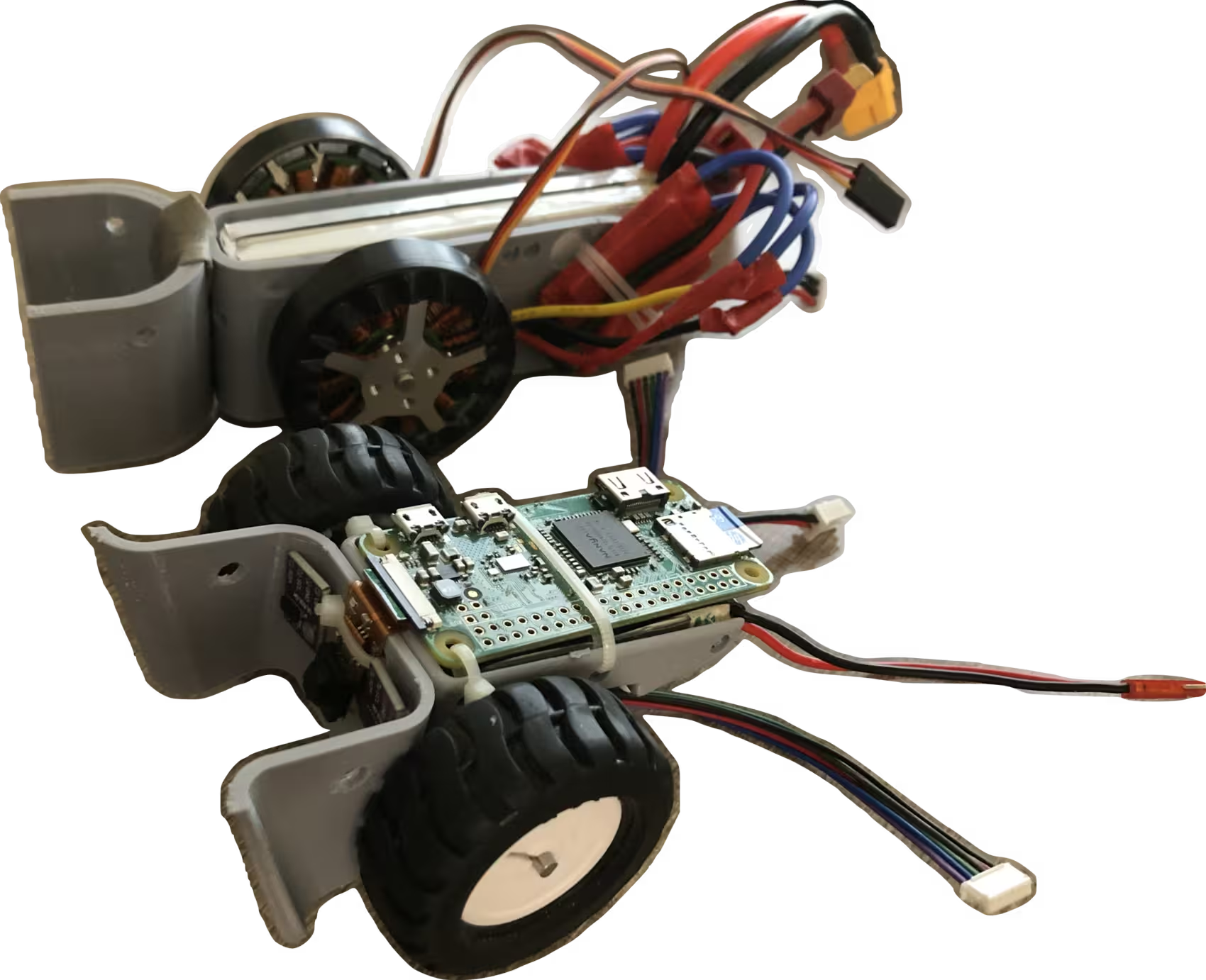

This version was tiny, smaller than the palm of my hand, about 9cm on the longer side, featuring N20 motors, a DRV8833, multiple ToF sensors (intended to allow calibration against walls), a Raspberry Pi Zero, an OV5647 Pi camera, a caster ball. The rulebook did limited changes between prelims and finals to “30%” (??), but since the original video had no real sense of scale, this passed the “inspection” step during the finals anyway.

Now, again, I didn’t have many days, but for some reason, I wanted to do everything in a “complete” manner. Computer vision to detect the blocks. Position estimation for inverse kinematics. State machines and pathfinding. Calibration and precision with PID control and sensory input. Location representation, pretty much a makeshift ECS. “Real robotics”.

For whatever reason, I was convinced that doing it this way was… morally superior? Or, no, the only option. I shooed away any easier and faster plan and kept tryharding.

It wouldn’t have been cheaty to do something far simpler, but I was:

- too rushed to actually finish the hard stuff,

- too stubborn to do the obvious (“cheaty”?) stuff, and…

- too tryhard to admit that the competition did not reward elegance.

While all it would have taken to have a winning robot was:

- a big, simple robot,

- with oversized claws,

- following a preprogrammed path with about three turns

- to push everything towards the hospital.

This blind yet unbeatable strategy would have brute-forced max points.

finals

Predictably, things didn’t work out, because code like this doesn’t “just happen” in a week of evenings, especially not when working with small robotics, with robots smaller than one’s palm…

On the finals day, things obviously are absolutely not working. I’m told I have to go, along with the rest of my previously uninvolved team. So I go.

My V2 robot’s wired up all intricate, with the Pi and a DRV8833, camera and ToFs, everything attached and nothing functional. It’s the morning and we’ve reached there, we’ve got maybe 20 minutes? I don’t remember, I’m writing this post much later in retrospect and looking back it’s still a bit fuzzy (hindsight is not 20-20).

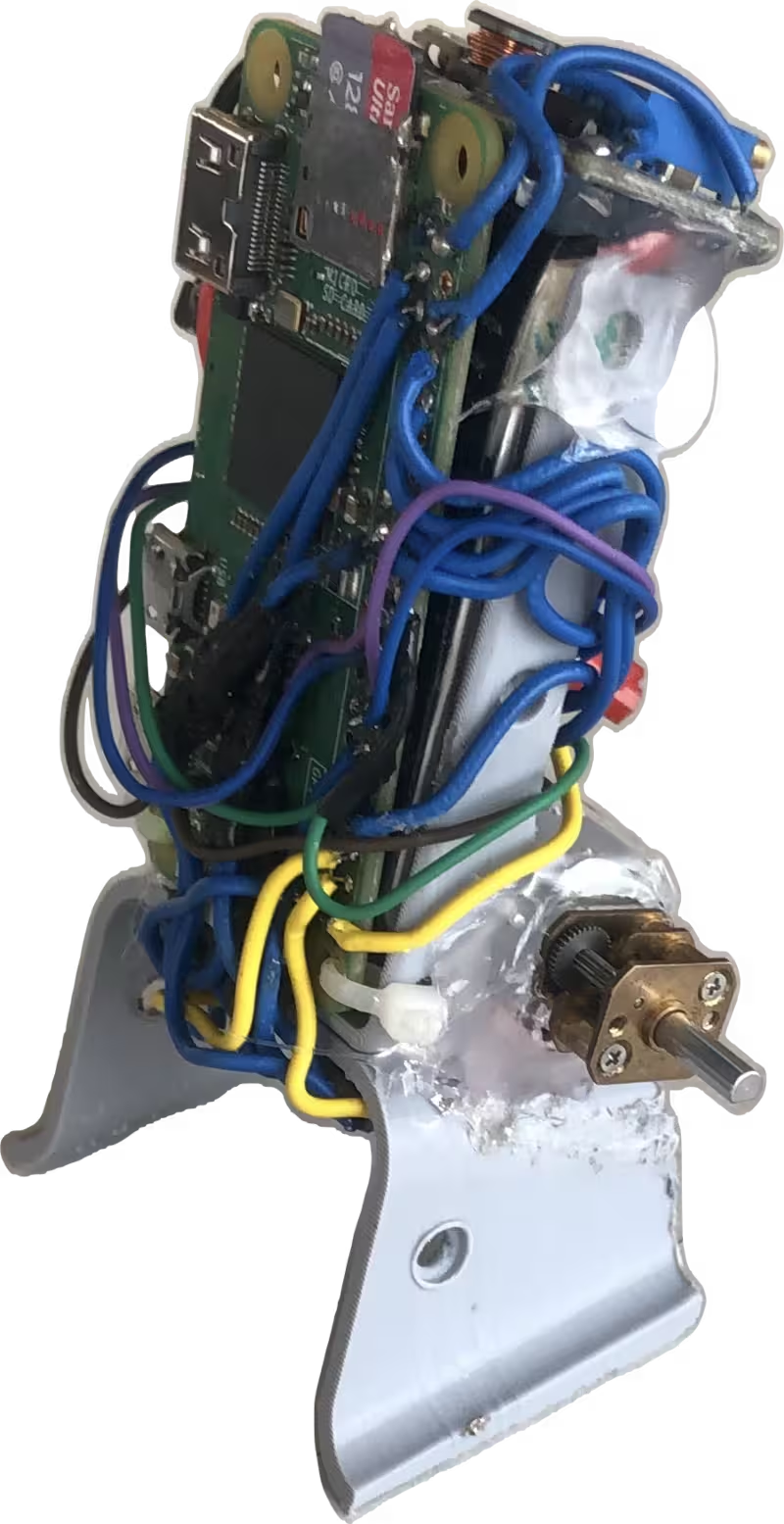

I’d brought an Arduino Nano, a TB6612FNG and my soldering set with me. Decide I’ve got nothing to lose and rip out the Pi’s connections, cold, while my iron warms, then stick the 328p in there with just power and the TB66 connected to it. I borrow glue and hide the Nano under the Pi, leaving the Pi connected to power and camera to make it look like it’s still driving operations.

Mind you, this is the smallest robot at the competition. So many of them are LEGO, something I’ve gotten used to seeing. I stop (with a thought about how they never win anyway) caring about the blatant violation of very explicit rules (think “KITS not allowed” and “LEGO MINDSTORMS not allowed”) from the rulebook. Future-me will look at the Swiss finalists and see they’re all LEGO. Internal agony will ensue.

Again, nothing I can do now. I borrow a laptop and program a quick fw, maybe three total lines of hurried code, to every two seconds change each of the two motor’s speeds to separate random values individually.

Great, I flash it onto the Nano with a dongle from an unexpected kindly figure.

My 9*4cm robot passes inspection.

I played four rounds at the gameboard.

With this random wheel speed code, I won three rounds.

The first round, the robot grabbed a block and took it to hospital on its own, completely out of the blue. What in the world?

I realized one motor was faster than the other, and the arc it made almost always pulled in the one closest block nearby, and since that was working for us, I decided to make sure of it.

Round two and three, I had a resistor (I found it on the ground somewhere…) on the slower motor’s driver to make it slower yet. Between mere minutes of quick soldering for repairs and unsafe charging methods to keep the battery going, each of these rounds, we ended with just one block in the hospital: one more, somehow, than any opponent’s.

I had some time before the fourth round. I decided to increase our odds while I could and preprogram a path to just sweep two or three into the hospital. With pizza, and now, unexpected help from a teammate, we got it pretty good. The physical claws on the robot still weren’t large enough to guarantee it given the lack of precision, but it was perhaps good enough to follow a path that ensured… three.

I wasn’t convinced. Scared, I panicked and changed it back to the random code. PRNG happened. It messed up, and we lost in the semifinal round.

out

I really remember how hard it hit on finals day. A blind robot with a path made well once would simply have had no room for error, even all exact block coordinates had already been given.

But TL;DR: In short, I qualified with a half-functional prototype, saw the simple and perfectly valid solution, knew it was viable, chose a harder path, built a whole new robot, failed to complete it, prayed to PRNG, passed inspection, beat most teams with chaotic motion, and somehow reached semifinals.

That’s just luck. I’ve been to dozens of competitions, and I hope to go a hundred more. But this one stings, like knowing the answer and still answering wrong.

Whelp!